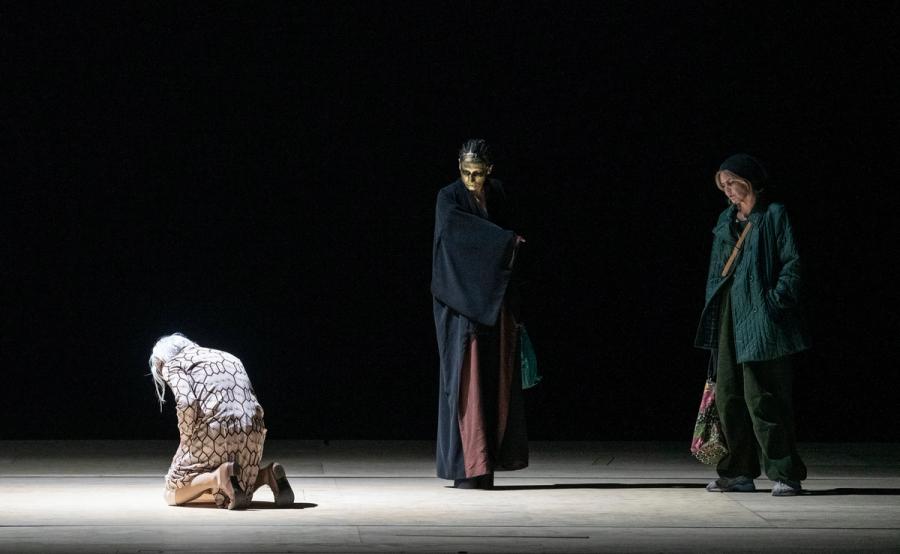

Created for the Norwegian National Ballet, Alan Lucien Øyen’s full-length work combines theatre, dance, and filmic storytelling, with original music by Alexandre Desplat. The production premiered at the Oslo Opera House in October 2023.

“I try to make theatre that the audience can take ownership of.”

– I have made several works for the Main Stage, but none as extensive as The Hamlet Complex. None as complex as the Hamlet complex!”

Alan Øyen laughs, and with that the entire Opera’s Studio C fills with warmth. He has a gift for this — creating an atmosphere that lets people relax around him, letting their shoulders drop.

Yet, though he presents himself as calm, the Bergen native at nearly two meters plus a couple of centimeters in Boston-Birkenstocks, his mind is full these days. Just yesterday he sat in the cafeteria with a serious expression, bent over his laptop in impenetrable concentration. Nothing Personal, his new full evening for the Norwegian National Ballet, premieres in eight days.

– Is Nothing Personal even more complex?

– You know, it is. It actually is. Unfortunately so.

The soul and the heart

He has gained a reputation for pushing the boundaries of what is possible on a stage. Every department at the Opera knows that when Alan conceives a new work for the Main Stage, it becomes grand.

Grand in the sense of detail. Nothing Personal is no exception.

– There are so unbelievably many parameters. Everything comes up and down from the floor, and you can imagine – the three wheels you have with numbers on the code lock can give infinite combinations, Alan says. – There is a lot of text, a lot of music, a lot of dance and scenography. Much that must be woven together. Much to keep track of.

He often refers to his team. “We” is behind this production. Some have worked closely with him for decades – the scenographer Åsmund Færavaag, for instance, and the actors in his own company winter guests. One of them, Andrew Wale, co-wrote the script. Another, Daniel Proietto, is co-choreographer and Alan’s extended arm. Several of the ballet dancers he has grown close to over his ten years as in-house choreographer.

Interview with Solrey, conductor of the music behind Nothing Personal

Music is by Alexandre Desplat – the two-time Oscar-winning film composer who now adds Nothing Personal to a CV that includes several Wes Anderson films, The Imitation Game, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Harry Potter.

– We got in touch some years ago when I was doing a production with the Paris Opera, Alan recounts. – Eventually it turned into a collaboration on a different project, The American Moth with winter guests. I’m very enthusiastic about Desplat’s universe. I almost have to pinch myself to get to work with him and bring his original music to the stage.

He describes the music as the engine of Nothing Personal, “the soul and the heart.” And with a scenographic world many have called cinematic, it makes sense that Alan has a film composer on board.

– Nothing Personal may lie closer to a film narrative than an opera or ballet. Short scenes, not longer than two written pages. Like films now – ninety seconds, and then you’re somewhere else.

– A hammer blow to the head

The entire stage arts world seems to want a piece from Alan Øyen. Last year he provoked and delighted with Cri de Cœur for the Paris Opera Ballet. winter guests toured Europe and North America. At home, The Hamlet Complex played to full houses and storming applause, before Alan directed the holiday show The Snow Sister at Det Norske Teatret.

He says he has taken a sabbatical year. But for Alan that means directing the Holocaust narrative If this is a manfor the National Theatre – and not least, the imminent world premiere of Nothing Personal.

The plan for what became Nothing Personal was laid years ago. The project was originally meant to be a staging of The Little Prince – until Alan stumbled upon an essay by James Baldwin. Yes, exactly: Nothing Personal.

– It was like a hammer blow to the head, as the Swedes say. It was like – POH! – straight to the liver, Alan recalls. – Baldwin wrote this essay in the ’60s, and it comments on his own era. It became clear to us that we had to create something that comments on our own era. And so we borrowed his title.

In the opening of the essay, Baldwin describes the stream of images he gets when switching between TV channels.

– It could as well have been a description of Tinder swiping addiction or Instagram rabbit holes, Alan says. – Without wanting to make a show about either Tinder addiction or the social media rabbit hole, or about James Baldwin – at least we wanted to create something that holds the time we live in. And look closer at the people who are falling a little outside society right now.

– What kind of time do we live in, really?

– A time that is quite scary to be present in. With tools that ironically are meant to bind us together – hypercommunication tools that in the ultimate consequence create less dialogue, less communication. Or, more communication which becomes noise. That is what is so fascinating; the concept of noise, monotony, and chaos are really the same thing.The book Ekko by Lena Lindgren is another source of inspiration.

– As Lindgren states in Ekko; the concept of chaos comes from “wasteland,” “void.” These things are connected.

Small chamber plays

The script has taken shape over the past few weeks, but the scenographic sketches were handed to the Opera’s workshops a year and a half ago.

– Already before we know which performance we will make, we draw up the framework for a universe, Alan explains. By “we” he means himself and his longtime scenographer and good friend Åsmund Færavaag, who according to Alan is engaged in much more than just the scenographic in a production. – We wanted to create a world that felt as golden as a desert, so we have built a desert out of wood.

The slanted pine stage may be the last remaining remnant of the idea of The Little Prince.

Set designer Åsmund Færavaag, talks about the complex work that went into the design and realization of the scenic design for Nothing Personal.

– Nothing Personal is a story with realism in it, and we wanted a chance to clean the slate, empty the floor, and have space for abstraction where parallel worlds can exist – click! – side by side.

Alan gestures. From this neutral desert, rooms, interiors, small separate universes emerge.

– Hopefully they can feel like small chamber plays inside a dance performance. We weave together dogmas and worlds that do not obviously belong together.

"I try to make theatre that the audience can take ownership of."

Together with Andrew Wale, Alan wanted to create what he calls an open text, where the audience can project their own understanding.

– For me, that is where the most exciting theatre lies – in the play between what I as an audience member feel it is, and what I am told it is on stage. Like when you read a book versus watch a film. In the book you draw your own set and faces on the characters, and in that way it is my book as much as it is the author’s. So I try to make theatre that the audience can have equal ownership of.

The storylines we follow belongs to a handful of people

A young girl lives her life on the internet and socializes only through her computer. An older academic has had a stroke and is losing his literary world.

An old woman struggles with anxiety and depression. It doesn’t get better when her psychologist tells her to “be better at practising coping strategies.” A young boy has locked himself in a room – hikikomori, the Japanese phenomenon where people choose to remove themselves from society. It simply becomes too much.

– Then we have a woman who has been raped, and who longs for her dead son, Alan adds. – And we talk a little about artificial intelligence.

Several references point to Greek mythology.

– The rape story is based on the myth of Philomela and Tereus. And we use a Greek chorus as backdrop – the coryphaeus, the chorus leader in Greek theatre, becomes a narrator binding this all together, hopefully. That is what we try to achieve. And so much dance. And so much text. You simply must be prepared that this will be theatre on the Main Stage in Bjørvika!

Alan and Andrew began writing the script one and a half weeks before the dress rehearsals in September.

– And why did we do that, you may ask. It would certainly have been easier to write the script in advance, and then just stage it.

Alan smiles.

– But I have arrived at this excuse for working that way, and it is that you should allow the process to influence the result all the time, along the way. Then I don’t make the show at home alone and push people around on stage; rather, we do it together from the first rehearsal day. Something one dancer says can become a monologue they get back. In that way they gain a completely different ownership of the material, together with the actors. The choreography may come from me, but also from the dancer in meeting what we work with.

Everyone involved has influence. Recently, a song was added into the performance. Åsmund, the scenographer, had listened to it in the car.

– He said “you have to hear this, this is nice.” Now it’s in the piece, Alan says. – So that’s how it works.

"Working like this, in this scale and format, is actually not really possible"

– Isn’t it frightening?

Knowing the dimensions of the scenography, but not what will play out inside it – only weeks before the curtain rises?

– Terrifying, Alan says. – People come up and say, “we have bought tickets, now there are only seven weeks to go.” At that point, to stand there with nothing, is frightening. And paradoxical. It’s really not possible to work like this in this format.

He compares it to pushing a train – working with productions as large as Nothing Personal.

– And you have to get that train up to speed before it rolls. It’s a heavy exercise. Right now we are there.

A little more than a week before premiere, Alan and his team are working to set the order of text, scenes, music. A demanding process, he admits.

– Kudos to the house, then! I am so grateful and proud of all that the Opera House accomplishes, when we work in such an unorthodox way. To be able to work process right up until the door closes behind the final audience member – it’s quite impressive to be allowed to do that.

The script is at least finished. The dogmas are outlined. And Alan, who is no stranger to venturing into the dark, can confirm that it is a tragedy they are in the process of staging on the Main Stage – albeit with a slanted gaze.

– Our times are pretty tragic, he laughs.

"To some extent, we're staging people’s nightmares."

– What do you think Nothing Personal will tell us?

– I always look for someone to come and kind of say “it’s OK” and put a hand on the shoulder. That is in a way the moral of everything we try to create; that life can be quite difficult and complicated, but it’s totally okay, really.

– So there is in fact some hope in this story?

– I hope so! I hope so. At least I hope there is tenderness. We stage people’s nightmares, largely.

He becomes serious – the choreographer, the director and playwright.

– It is quite brutal and violent how we get to see what goes on inside the heads of those who struggle most. And as human beings we can be terribly unkind to ourselves. So I hope that at the very least we remain with a kind of … sometimes it is nice to hear how people are doing. For real, not just the masks we wear. Let’s take off those masks, then, be a bit honest. Even if not everything behind the mask is pretty.

Now he smiles again. A glance at the clock prompts me to thank him for the talk. After all, Alan has a Main Stage production to finish.

– That works well, he says, looking at his smartphone. – Daniel [Proietto] is down in the cafeteria wondering when we're going to finish the second act.

Alan Lucien Øyen talk about the process behind Nothing Personal.